Andrew J. Hewitt, PMHNP-BC

Abstract

High-profile retirements can function as cultural mirrors—inviting everyday people to reflect on identity, purpose, and the psychology of “what’s next.” John Cena’s decision to step away from full-time in-ring competition (and close out a farewell run) offers a useful framework for men navigating transitions: retirement, career changes, divorce, empty nest, injury, aging, or simply a growing sense that an old role no longer fits. This blog uses Cena’s retirement as a real world example of healthy “moving on,” integrating recent (2024–2025) research on athlete career transitions, retirement related meaning, social identity shifts, and the impact of masculinity norms on help-seeking. Practical, evidence-aligned strategies are provided to help men reduce anxiety and depression risk during major life transitions by strengthening identity beyond one role, building purpose, sustaining connection, and seeking support early.

Introduction: Why a Wrestler’s Retirement Can Hit So Deep

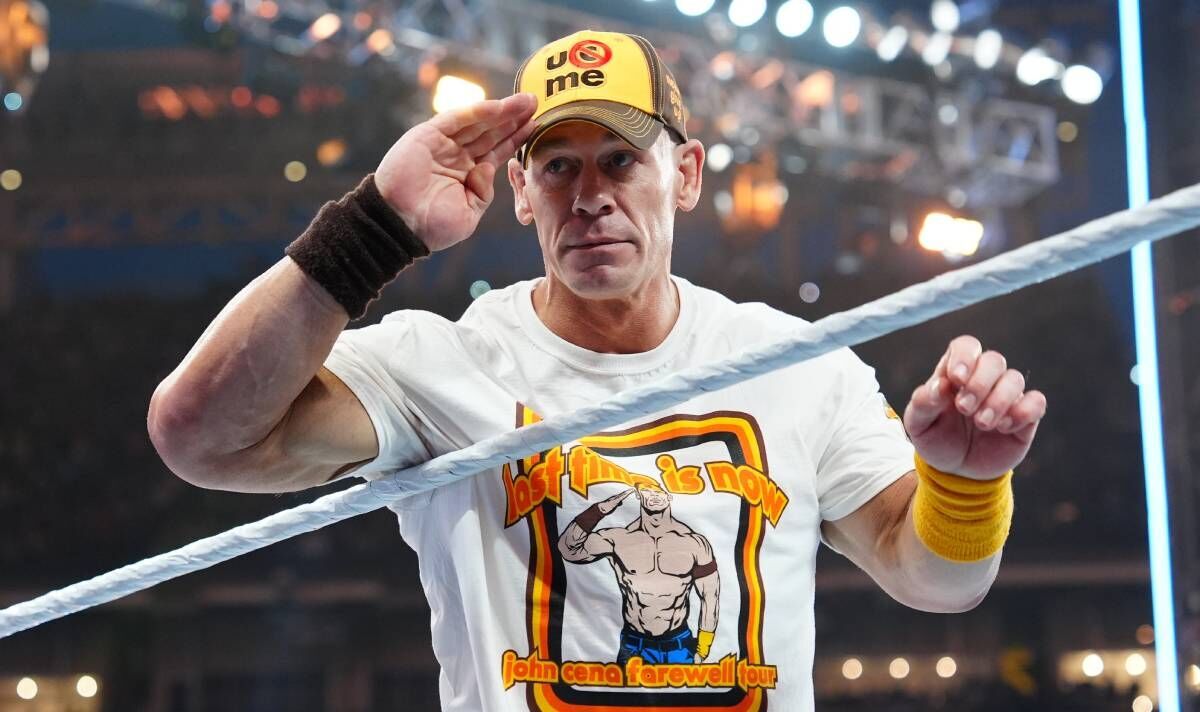

When John Cena announced he would retire from in-ring competition in 2025, it resonated far beyond wrestling fandom. WWE framed it plainly: after a legendary run, he would step away from that chapter and finish on his own terms. WWE Mainstream sports media similarly highlighted the announcement and the significance of the transition. ESPN.com

From a psychiatric perspective, it makes sense that this kind of moment lands with men in particular. Many men, whether athletes, veterans, business owners, fathers, or providers… anchor self-worth in a role: “what I do” becomes “who I am.”

When a role changes (by choice or by force), the mind often scrambles to stabilize identity. That scramble can look like irritability, insomnia, increased drinking, emotional shutdown, risk-taking, or quiet depression; symptoms that can be missed because they don’t always look like sadness.

Cena’s story provides a healthier model: plan the transition, honor what was, and move toward what’s next with intention. That’s not just inspirational, it’s clinically useful.

The Psychology of “Retirement” (Even If You’re Not Retiring)

In research, “retirement” is a major life-course transition tied to changes in routine, identity, social structure, and meaning. A 2025 overview of systematic reviews noted that retirement’s effects on mental health vary widely, influenced by socioeconomic factors, job characteristics, and lifestyle, but the transition itself is a meaningful stressor because it disrupts identity and daily structure. ScienceDirect

Even if you’re 32 and changing jobs, or 45 and stepping out of a leadership role, the psychology is similar:

- Loss of structure (days become less defined)

- Loss of community (coworkers/teammates drift)

- Loss of status (less recognition, fewer “wins”)

- Identity destabilization (“If I’m not that guy anymore, who am I?”)

A 2025 scoping review in The Gerontologist emphasized meaning as a central variable in retirement adjustment, people do better when they can build a coherent “why” for the next chapter. OUP Academic

Athlete Retirement Research: What It Reveals About Men’s Mental Health

John Cena is not an “ordinary retiree,” but athlete transition data is valuable because it magnifies identity issues that many men experience more quietly.

Risk: Anxiety and depression can rise after the spotlight dims

A 2024 systematic review and meta analysis in BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine concluded that former elite athletes can have roughly twofold increased incidence of anxiety and depression compared with the general population. BMJ Open Seminars While “elite athlete” isn’t the same as “everyday man,” the mechanisms overlap: role loss, identity foreclosure, pain/injury, sleep disruption, and a sudden shift in social reinforcement.

What protects mental health during transitions?

A 2025 systematic review on correlates of athlete mental health during career transitions synthesized quantitative evidence across many transition types and outcomes, highlighting the importance of planning, identity breadth, social support, and coping resources. Taylor & Francis Online In plain language: men do better when they don’t let one identity (job, sport, rank, “provider”) crowd out all others.

A separate 2025 commentary introduced “athletic retirement literacy,” emphasizing competencies like preparation, emotional skills, social support, and meaning, making skills that generalize well to non-athletes facing major change. Taylor & Francis Online

Cena as a Case Example: The Healthy Mechanics of Moving On

WWE’s official coverage described Cena’s planned exit from in-ring competition and positioned it as a deliberate close to a major chapter. WWE That matters. Transitions tend to be healthier when they include three ingredients:

- Narrative closure (“This chapter mattered.”)

- A future-facing identity (“I’m becoming someone, not disappearing.”)

- Connection and continuity (support systems remain intact)

For many men, the painful part of moving on isn’t the change itself—it’s the fear that moving on means the past wasn’t meaningful. In reality, psychological health improves when you can hold both truths: that was real, and I’m not trapped there.

The Masculinity Factor: Why Men Struggle to Ask for Help

Transitions are hardest when men are taught they must handle them alone.

A 2025 systematic review on traditional masculinity norms and mental health help seeking found consistent links between stronger endorsement of certain masculinity norms and reduced willingness to seek psychological support. SAGE Journals Related 2025 work also examined how gender norm conformity influences men’s help-seeking and treatment engagement, reinforcing the pattern that “toughing it out” can become a barrier to care. Taylor & Francis Online

The American Psychological Association also highlighted that rigid masculinity norms can harm boys’ and men’s mental health, and called for healthier models rooted in connection, authenticity, and resilience. American Psychological Association

This is where Cena’s public persona is relevant. His brand has long emphasized discipline and grit, but retirement represents another kind of strength: adaptability. The ability to pivot without collapsing is mental fitness.

How “Moving On” Helps Men’s Mental Health

When done intentionally, moving on supports mental health in several evidence-consistent ways:

1) It reduces identity foreclosure

If your identity is fused to a single role, stress increases when that role is threatened. Expanding identity (partner, dad, coach, artist, learner, community member) reduces psychological fragility. Transition research consistently flags identity breadth as protective. Taylor & Francis Online

2) It restores meaning and agency

Meaning buffers stress. The retirement meaning literature emphasizes that a coherent sense of purpose improves adjustment and wellbeing. OUP Academic “I’m choosing my next chapter” is psychologically different from “I’m being replaced.”

3) It keeps social connection alive

Retirement and role transitions can increase isolation, which is strongly linked to worse health outcomes. A 2025 study using ELSA data examined the relationship between retirement and loneliness/social isolation, underscoring the importance of social continuity during transitions. SpringerLink

4) It improves emotional regulation under stress

A 2024 study (HEARTS, Sweden) examining depressive symptoms across retirement transitions in men and women linked outcomes to factors like work centrality and emotion regulation strategies (e.g., suppression vs. reappraisal). SpringerLink Men who rely heavily on suppression often appear “fine” until they aren’t, then symptoms show up as anger, withdrawal, or substance use.

Practical Strategies: The “Cena Transition Plan” for Real Life

You don’t need a retirement tour to transition well. Here’s a clinically grounded framework I use with men in therapy and medication-management settings.

Step 1: Name the role you’re leaving—and what it gave you

Write two lists:

- What the role gave you (status, routine, brotherhood, pride, money, identity)

- What it cost you (sleep, health, relationships, peace)

This creates narrative closure rather than emotional avoidance.

Step 2: Build a “next identity” in three pillars

Pick three identity anchors that will remain stable even if work changes:

- Body (training, walking, medical follow-ups)

- Bond (relationships, men’s group, faith/community)

- Build (learning, hobby, volunteering, entrepreneurship)

Athlete-transition research supports preparation and identity breadth as protective. Taylor & Francis Online

Step 3: Replace structure before you lose it

Transitions become mentally destabilizing when days lose shape. Schedule:

- Wake time

- Movement

- Social touchpoint

- One daily “win” task

- Wind-down routine

Retirement overview evidence emphasizes routine, activity, and social identity as key factors in mental health around retirement. ScienceDirect

Step 4: Watch for “quiet depression” and “loud anxiety”

Men’s depression often shows up as: irritability, numbness, sleep disruption, low motivation, increased substances, or anger. Anxiety can show up as control seeking, rumination, and constant “next problem” scanning.

If symptoms persist for more than two weeks or impair function, it’s time for support.

Step 5: Practice help-seeking like a skill (because it is one)

If masculinity norms make therapy feel uncomfortable, start with “low-barrier” steps:

- A single telehealth consult

- A structured assessment (GAD-7/PHQ-9)

- Skills coaching (sleep, stress response)

This matters because masculinity norms are empirically linked with reduced help-seeking. SAGE Journals+1

When Medication Can Help (and When It’s Not the First Answer)

Some men need medication support during transitions, especially when anxiety, panic, insomnia, or depression become clinically significant. In those cases, a PMHNP can help evaluate:

- whether symptoms meet criteria for a disorder,

- whether substance use is complicating mood,

- sleep patterns and medical contributors, and

- treatment options (therapy, lifestyle, medication, or a combination).

Medication isn’t a substitute for meaning, connection, and identity rebuilding, but it can lower symptom intensity enough to do the deeper work.

Conclusion: Retirement as a Blueprint for Emotional Strength

John Cena’s retirement is more than a sports story. It’s a culturally visible example of something many men must learn the hard way: moving on is not quitting… it’s evolving.

Research from the past two years is clear on the underlying themes: transitions challenge identity and meaning, isolation worsens outcomes, rigid masculinity norms inhibit help-seeking, and preparation plus social support improves adjustment. Taylor & Francis Online+3ScienceDirect+3OUP Academic+3

If you’re in a “Cena season” of life closing a chapter, changing roles, redefining yourself; take it seriously, and take it compassionately. You don’t have to do it alone. And you don’t have to wait until things break to start rebuilding.

References (APA 7th)

American Psychological Association. (2025, September 23). Rethinking masculinity to build healthier outcomes. Monitor on Psychology. American Psychological Association

Gouttebarge, V., Bindra, A., Blauwet, C., et al. (2024). Prevalence of anxiety and depression in former elite athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 10(4), e001867. BMJ Open Seminars

McCluskey, T., Stevens, M., Cruwys, T., Murray, K., & Freeman, H. (2025). Correlates of athlete mental health during career transitions: A systematic review of quantitative research. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology. Taylor & Francis Online

Nilsson, L. G., et al. (2024). Depressive symptoms across the retirement transition in men and women: Associations with emotion regulation strategies, adjustment difficulties, and work centrality. BMC Geriatrics. SpringerLink

Schinke, R., & colleagues. (2025). A commentary on high-performance athletes’ retirement and mental health: Introducing athletic retirement literacy. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. Taylor & Francis Online

Wood, R. E., & Pachana, N. A. (2025). The role of meaning in the retirement transition: A scoping review. The Gerontologist, 65(6), gnaf076. OUP Academic

Zhang, X., & colleagues. (2025). Impact of retirement transition on health, well-being, and health behaviours: An overview of reviews. Social Science & Medicine. ScienceDirect

Zhou, Y., & colleagues. (2025). The relationship between retirement, social isolation and loneliness: Evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. BMC Public Health. SpringerLink

World Wrestling Entertainment. (2025). John Cena announces that he will retire in 2025. WWE.com. WWE

ESPN. (2024). John Cena announces upcoming WWE retirement in 2025. ESPN.com